India’s second Covid-19 surge

India’s devastating Covid-19 surge earlier this year personally affected Indian immigrants all over the world. Many had family members or close friends who contracted Covid. My wife and I have family in Mumbai and in India’s north-east. We have several friends and their families all over the country. By early March we were very concerned as we learned about the rapid rise in cases in parts of Maharashtra state (home to Mumbai) and the difficulty in accessing hospital services, well before international news media had begun extensive reporting (notably, the BBC had reported on a possible surge at the end of February). And then as India’s coronavirus spread spiralled out of control we followed developments with distress and anxiety. Videos making the rounds on WhatsApp from crematoriums and hospitals horrified us. While previously we knew someone who knew someone who had contracted Covid in India, now we directly knew of several people who had Covid or had a family member infected or who had died from the disease.

But was India’s Covid surge unexepected?

Much has been reported over the past couple of months, particularly regarding whether the spread of coronavirus in India in what became a deadly second wave was extraordinarily unpredictable. I personally wanted to look back at the data to get a first hand look. Here goes.

The surge

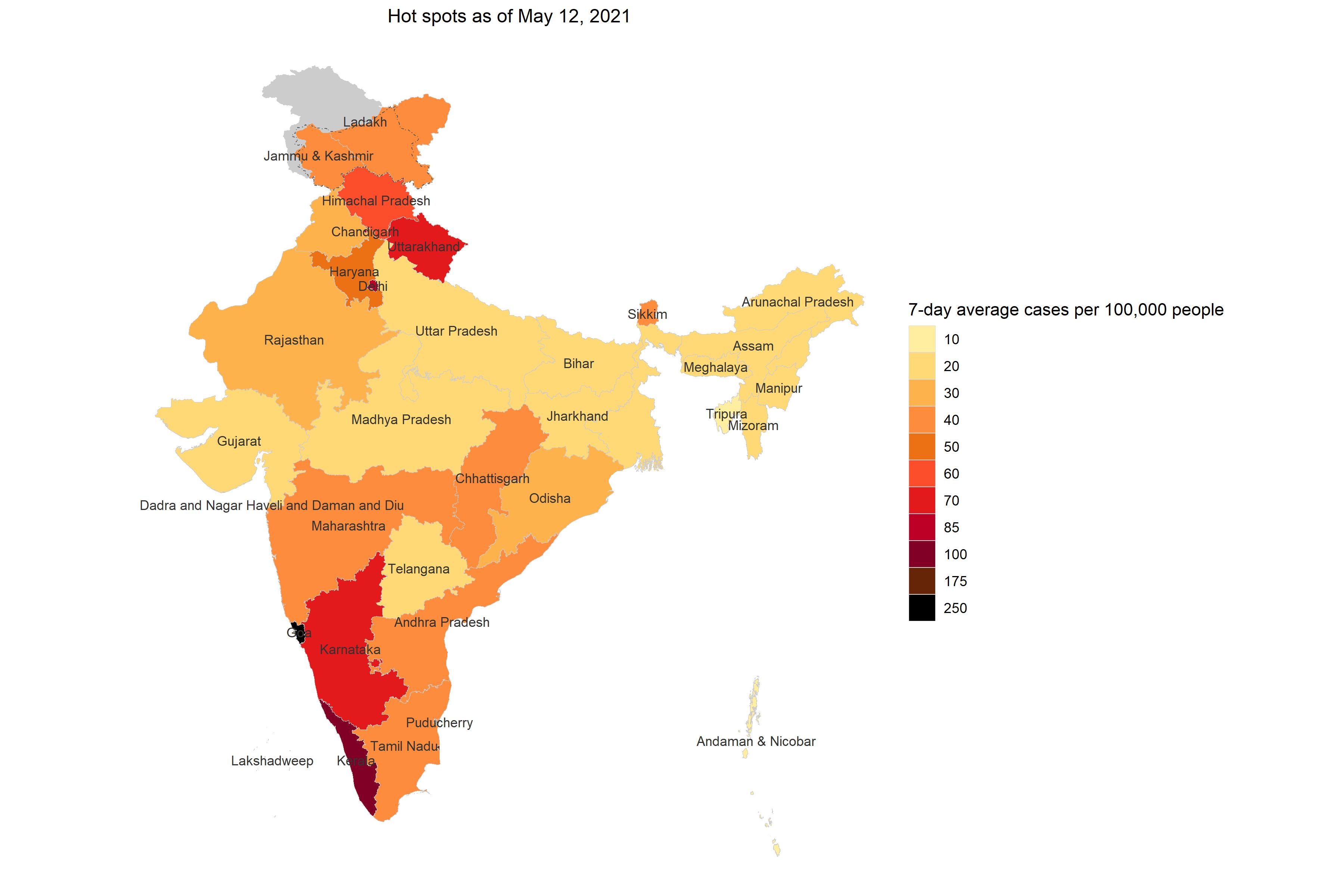

In mid-March Covid cases were steadily increasing across India, particularly in the states of Maharashtra and Kerala. By early April it was clear the novel coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, that causes Covid-19 was on a rampage in India. By the beginning of May it seemed hopeless. India was bleeding all over as seen in the case rate (7-day average of daily cases per 100,000 people) visualized on May 12, 2021.

On the ground, this was playing out in real time in India’s hospitals, crematoriums, burial grounds, homes, and on the streets. People couldn’t get medical care for their loved ones as hospitals were way past capacity. If you did manage to get into one, healthcare staff that was already exhausted and working round the clock could barely keep up and provide the personalized attention needed for such a virulent disease. Medical oxygen supplies and ventilators (necessary to help control respiration in acutely compromised cases) were scarce. Crematoriums were running at full capacity and makeshift crematoriums cropped up in parking lots and public spaces.

But this wasn’t an overnight happenstance. How did India get to this point?

Lockdown 1.0

In the intial days of the Covid-19 pandemic the Indian government implemented one of the most aggresive lockdowns. On March 24, 2020 Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced a 21-day lockdown, curtailing the movement of the entire population. India had about 500 confirmed Covid-19 cases at the time.

I grew up in Mumbai on a street that was a near microcosm of the city. We were a household of 5 living in about 600 sq. ft. Within a 3km radius (~ 2 miles) you had a stratified view into wealth and income disparity, cultural and regional identities, abundance and lack of access to water and sanitation, spacious bungalows and overcrowded shoebox apartments –– a reflection of the continual cauldron of contradictions that is India. Overcrowded living quarters and status-dictating access to water is the norm in India’s mega cities and common elsewhere.

So, while the western world debated the specifics of social distancing and frequent hand washing and stay-at-home orders, I just didn’t see how India or other densely populated and poorer countries could realistically comply. Social distancing in a country of 1.3 billion –– more than three times the U.S. population living in about 1/3rd the size of the U.S. –– was a non-starter. Residential living density in most places would probably violate most U.S. zoning laws. Where consistent access to sanitation and water is generally on a sliding privilege scale, frequent hand washing was a tall ask.

But people largely complied with lockdown orders (the government did face criticism over its lockdown implementation in the space of 5 hours that left migrant workers and day laborers stranded, causing them to move back to their villages enmasse, which then created a superspreader event). Photographs of deserted streets in India’s cities were surreal. When they did move out, people wore masks for the most part and police enforced mask wearing as it would enforce a nightly anti-terrorism checkpoint.

Then came complacency

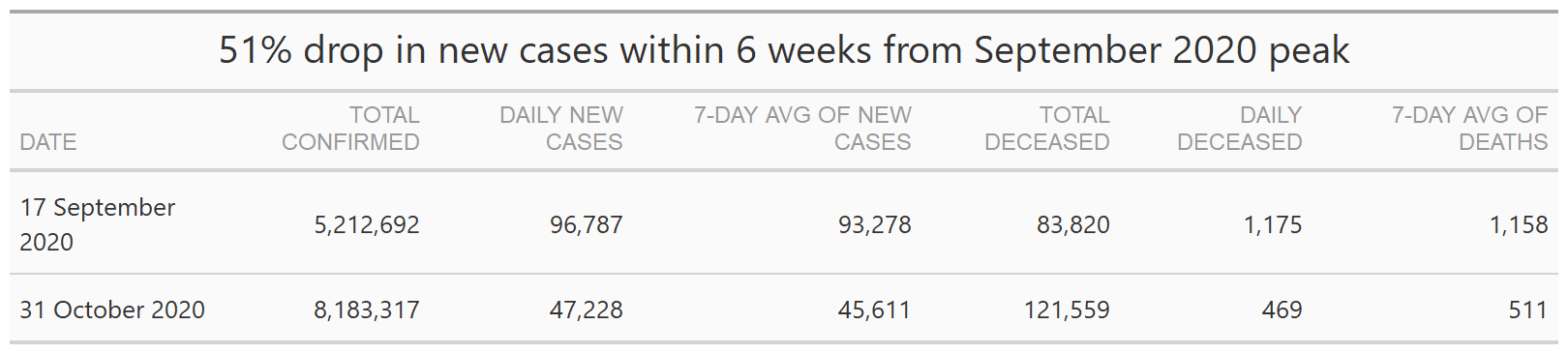

After the peak in September 2020, something changed. While in the U.S. we were hitting post Labor Day surges and worried about a calamitous surge if people traveled with abandon to meet loved ones over the Thanksgiving and Christmas holidays, my opinion of the sentiment in India was that many people had concluded India was almost free of coronavirus. Based on a remarkable drop in reported cases and deaths (from the mid-September 2020 peak to October 31, 2020, India reported a 51% drop in the 7-day average of daily new cases and a 56% drop in in the 7-day average of daily deaths), one could maybe understand the optimism of people.

The Indian government further stoked this optimism by putting India into “Unlock 6.0” (the last of a series of unlock stages) –– swimming pools, movie halls, entertainment parks, weddings, religious and political events and more were permitted to operate with varying capacities. India was ready to celebrate the end to 2020 with Diwali, Christmas, and New Year’s Eve. In December 2020, the Reserve Bank of India declared “India is bending the COVID infection curve” and was ready to charge up the economy.

Personally, I was learning about Indian residents living overseas traveling back to India for extended visits with family (especially as remote work had become the norm). It was preferable for them to be out and about in India than be under stay-at-home orders or lockdown in their countries of residence.

But was this optimism misguided? Was the data reliable?

In September 2020, before India hit its first Covid-19 peak, an article in the Lancet questioned the lack of transparency and deficiencies in India’s testing methods and classification of Covid-19 deaths.

I was scratching my head.

Political braggaddocio

On January 28, 2021, Prime Minister Narendra Modi extolled India’s fight against Covid-19 in his address to the World Economic Forum’s Davos Dialogue via teleconference.

“Friends, I have brought the message of confidence, positivity and hope from 1.3 billion Indians amid these times of apprehension…It was predicted that India would be the most affected country from corona all over the world. It was said that there would be a tsunami of corona infections in India, somebody said 700-800 million Indians would get infected while others said 2 million Indians would die. The world’s concern for a developing country like India was also natural given the state of affairs in the world’s greatest countries with modern health infrastructure…But India did not allow itself to be demoralized. Rather India moved ahead with a proactive approach with public participation. We worked on strengthening the Covid specific health infrastructure, trained our human resources to tackle the pandemic and used technology massively for testing and tracking of the cases.”

–– Prime Minister Narendra Modi, WEF 2021

Modi’s words almost appear to show a faint appreciation for the concern of health professionals and epidemiologists from nations with modern and sizable health care infrastructures who had already faced the realities and consequences of reaching healthcare capacity. What would happen if (when?) a surge struck India? With its abysmally low healthcare spending (about 1.3% of GDP) –– 1 doctor per 1,456 residents (when considering only government hospital doctors, typically the only medical access in rural areas, it is 1 doctor per 11,000 residents), 2.3 intensive care beds per 100,000 people (most concentrated in 7 states), an estimated 40,000 ventilators (only about 8,400 in the public sector) –– would India be able to withstand a Covid-19 situation on a scale experienced by Italy or the United States?

But Modi’s tone did not strike compassion or empathy for any of the European countries or the United States for their pandemic struggles or concern for India. Just arrogance. In Hindi there are several words for the subtleties of egotism and pride –– ahankar and abhiman come to mind.

In Modi-esque fashion, he went on:

“Friends, it would not be advisable to judge India’s success with that of another country. In a country which is home to 18 percent of the world population, that country has saved humanity from a big disaster by containing corona effectively.

In the initial period of Corona, we were importing masks, PPE kits and test kits…And today it is India which has also launched the world’s largest corona vaccination program….In just 12 days, India has vaccinated more than 2.3 million health workers. In the next few months, we will meet the vaccination target of about 300 million elderly and co-morbidity patients.”

Then on March 7, 2021 Union Health Minister Dr. Harsh Vardhan speaking at MEDICON 2021, Delhi Medical Association’s state medical conference, ran a victory lap in India’s Covid-19 pandemic fight.

“We are in the ‘end game’ of the Covid-19 pandemic in India…Unlike most other countries we have a steady supply of Covid-19 vaccines…”

–– Union Health Minister, Dr. Harsh Vardhan

Interestingly, “end game” is a term in chess (chaturanga is the ancient Indian ancestor of modern chess) when there are few pieces left on the board. I wonder if Vardhan was alluding to an analogy here. If so, based on what?

The world’s pharmacy

On January 1, 2021 India’s drug regulator, Central Drugs Standard Control Organization (CDSCO), approved two Covid vaccines for use –– Covishield developed by AstraZeneca-Oxford University and manufactured by the Serum Institute of India and Covaxin developed indigenously by Bharat Biotech. Notably, Covaxin had not completed phase three trials at the time of approval.

India, as the world’s largest manufacturer of vaccines and medicines, is often referred to as the “world’s pharmacy.” Without doubt Indian pharmaceutical companies have been critical in saving lives in poorer countries around the world by making available low cost vaccines and generic drugs to combat diseases such as AIDS, malaria, and tubercolosis. With the spread of coronavirus, India was again expected to play a major role in vaccine production.

But officials in India weren’t quite prepared. They seem to have misjudged the development timeline and caught on the backfoot by the rapid approval process for the Covid-19 vaccines. They didn’t seem to have a plan matching production to demand, domestically or for export. In fact, domestic demand was very low until the second Covid surge had a stranglehold on the country. People weren’t “vaccine hesitant” but in “vaccine deferment” mode. They probably figured there may not be a need to get vaccinated if India is on its way to naturally being rid of the coronavirus. And then there was the miscalculation regarding the availability and procurement of raw materials for vaccine production.

Vaccine diplomacy

Notwithstanding the reality of India’s inability to produce vaccines to meet demand, in January 2021, euphoric with India’s low rate of Covid cases, Modi’s government emabarked on “vaccine diplomacy” gamesmanship. While other countries prioritized vaccinating their populations, Modi decided to project India’s regional importance by exporting Covid vaccines to other countries, even while its domestic vaccination was in a nascent state. According to government data, India exported about 66 million doses between January and April 2021. While this could be construed as noble intent, the unfortunate reality is that the Modi government gambled on the then lack of urgent need domestically to show geopolitical might. Vaccinating the domestic population aggressively just never seemed to be a priority given the low number of cases early in the year.

Indian exceptionalism

Reading messages on Indian group chats on WhatsApp, learning about people traveling in India, and parts of Indian media coverage proclaiming a quick return to normalcy, I was perplexed how public sentiment had turned to “it’s okay now to go back to pre-Covid times.” How had so many Indians figured things had gone back to normal? That coronavirus was not something to be concerned about. That India had defeated Covid while other governments were focused on getting their people vaccinated and avoiding yet another surge.

The Modi government again perpetuated Indian exceptionalism as a differentiating factor. Indians readily embraced it.

- Demographic advantage That a significantly younger population (46% of Indians are under the age of 25 years and only 6% are older than 65) served as a firewall against spread of the disease. Even if people in this group contracted Covid they had recovered and would recover quickly (this completely overlooks the issue of Covid long haulers –– where people who had had Covid and were no longer positive but months later were just not their former selves, experiencing foggy minds, unusual fatigue, and other symptoms).

- Geographic advantage That a large rural population (65% of the population lives in rural areas) prevented rampant spread of the disease. (Did enough testing substantiate this claim?)

- Super immunity That as Indians are exposed on a daily basis to low-hygiene situations and environmental contaminants in air, water, and food, and are largely habituated to, have a stronger immune response in general –– a classical ecological correlation misrepresented as an explanatory causative linkage. The problem: this is not unique to India.

- Herd immunity That a large percentage of Indians had already caught Covid but had been asymptomatic, and therefore, India had achieved herd immunity. (a “supermodel,” developed in September 2020 and commissioned by the government’s Ministry of Science and Technology, predicted India had reached “herd immunity with about 380 million people already infected.”)

- BCG vaccine That the BCG vaccine (used to prevent tuberculosis) many Indians receive in childhood conferred immunity against Covid (even though this made little sense as India had already experienced its first peak in September 2020).

India’s second wave

The political hubris could be attributed to the sharp (but unexplained) drop in reported Covid-19 cases since September 2020.

- India’s 7-day average of daily new cases fell from a peak of over 93,000 in mid-September 2020 to below 20,000 on December 31, 2020.

- On February 15, 2021 India reported 9,086 new cases, the 7-day average of daily new cases was just over 11,000, and the 7-day average daily deaths caused by Covid dropped below 100.

But what is interesting to note is that on March 5, 2021 (two days before Vardhan’s “end-game” remarks), India’s 7-day average of new cases had steadily ticked upwards to over 16,000 –– a 44% increase in 18 days!

Public complacency could be attributed to misguided Indian triumphalism intermingled with an apathy for data evidence, the experience of other nations, and expert opinion of health care professionals.

More importantly, absence of evidence is not evidence of absence.

India’s case count

![]()

The key here is “reported” cases. This assumes India was testing sufficiently…all around the country. Tracking variants effectively. Regardless, just with the official tally it is clear that Covid-19 had not left India, even if Indian politicians wanted to believe otherwise.

Superspreader events

Even with the government’s offical data (that is widely considered an undercount) it was clear by mid-March that India had a wildfire and needed to act. Instead Covid infections were fueled by the Indian government failing to acknowledge the data and maintain an urgency around testing and vaccination and people letting their guard down, choosing to engage in social, religious, and entertainment events.

![]()

The surge timeline

- At the end of February, the Election Commission of India announced voting for Phase 1 Assembly elections starting on March 27, 2021 in West Bengal and Assam, followed by Tamil Nadu, Kerala, and Puducherry. Complicating things further was the government’s decision to allow election campaigning and rallies with large crowds.

- At March end Indians widely celebrated Holi –– a religious festival heralding the arrival of spring where people smear each other with colors and water.

- In March and April, 2-3 million people (largely without masks or any kind of social distancing) congregated for the Kumbh Mela –– a religious festival celebrated every 12 years –– at locations in the states of Uttarakhand and Uttar Pradesh. The Modi government characteristically did not ban this religious gathering of Hindus, while in April 2020 it had unequivocally characterised an Islamic evangelical group’s gathering of 3,000 members from all over India as a superspreader event (which it was).

- In mid-March, while Covid cases were rising in Gujarat, officials allowed cricket-obsessed spectators to attend matches between India and England for two days. Even with a 50% capacity limit, about 60,000 people per day flocked to the stadium not adhering to social distancing and not wearing masks.

- In mid-April 2021, even with the surge escalating, Home Affairs Minister Amit Shah maintained that election rallies could not be blamed for the rise in Covid-19 cases.

Clearly, the large gathering of people for Kumbh Mela over a period of a month, the election rallies, Holi celebrations across the country are susperspreader events that correlate with the rise in Covid cases. But, also important to note is that in a country with India’s population, population density, and residential overcrowding, pretty much daily life is a superspreader event. Mumbai started its local (commuter) rail service on January 29, 2021. Right away people were riding in overcrowded trains. If one member in the household contracts Covid it is impossible for the average Indian home to isolate the person – there simply isn’t enough square footage. And so, as it played out, entire families were contracting Covid, especially with the delta variant discovered in India.

Warning Signs

The Indian government set up Indian SARS-CoV2-Consortium on Genomics (INSACOG) –– a forum of scientific advisors from ten national laboratories –– in December 2020 to monitor and detect coronavirus variants of concern with genomic sequencing and their threats to public health. INSACOG reported the B.1.617 variant to the health ministry’s National Centre for Disease COntrol (NCDC) in early March 2021. In a press release, the Indian government appears to have downplayed any concerns that may have been raised. A Reuters report in April 2021 suggests the Indian government ignored INSACOG’s warnings about B1.617.

It is interesting that a consortium set up by the government was marginalized by the government.

The storm

The second Covid-19 surge took India by storm. It surprised the medical community in its transmiissibility and severity and its catastrophic effect on healthcare infrastructure, most notably in the shortage of hospital beds, medications, and medical oxygen.

India’s death toll

![]()

Note: Large single day spikes in daily deaths in 2020 are the result of reporting errors or delays in reporting.

Surge in major cities

![]()

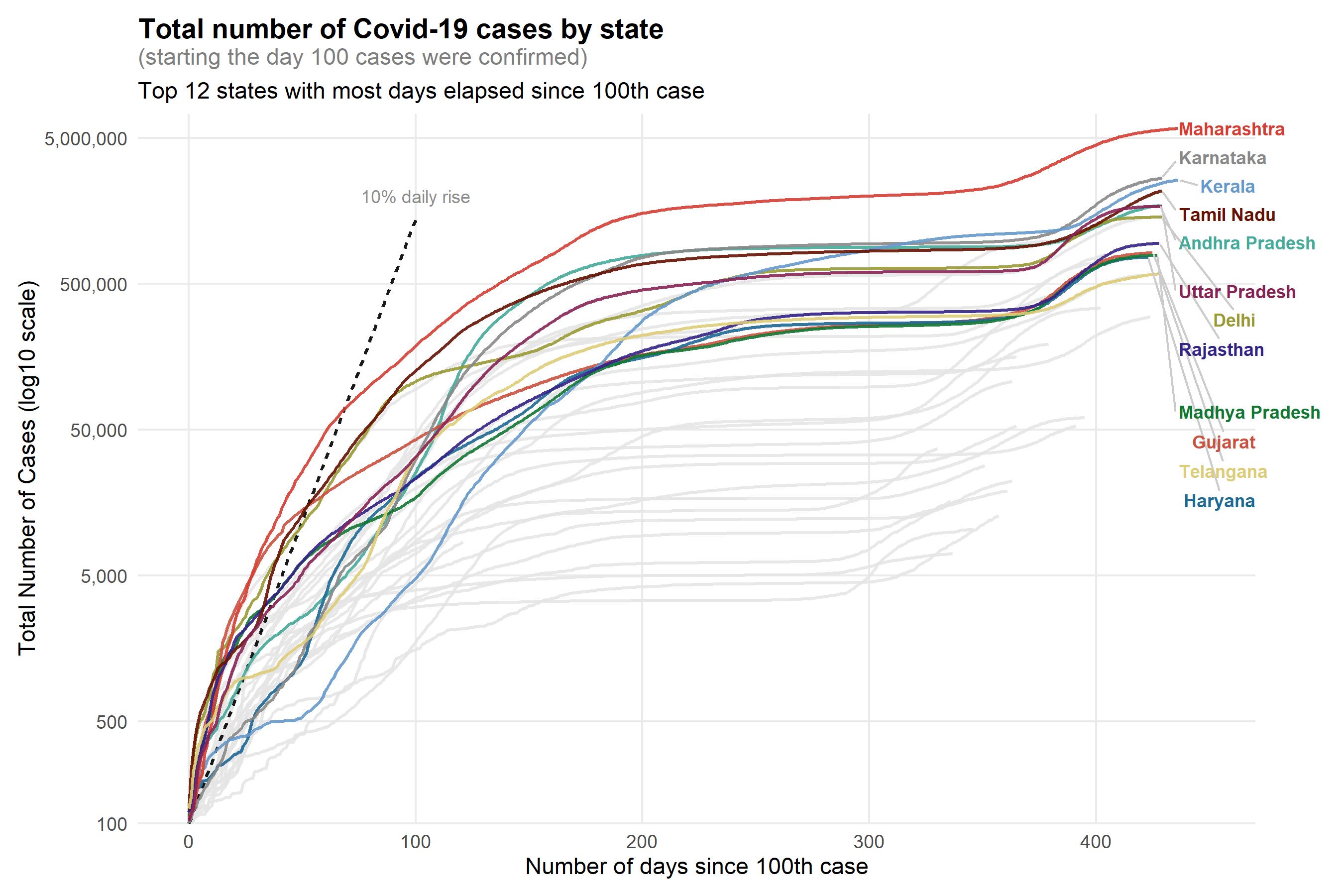

Rate of spread

Visualizing the number of Covid-19 cases by days elapsed since 100th case reported using a log10 scale shows the exponential spread of the disease. (A log10 scale on the Y axis means values 100, 1,000, 10,000 and so on are equi-spaced, which helps illustrate the exponential rate of spread). The first surge shows a dramatic spke in cases right after the 100th case. The second surge about a year later, at about 375 days since the 100th case, again shows a rapid growth rate.

What did the data show?

It is always illuminating to recreate a timeline with the data that was available to understand if there were enough early indicators or signals that warranted attention. To assess if the existing data did have sufficient value to trigger extensive analysis which could have helped determine aggresive intervention or policy shifts.

So, let’s see what the data showed early on.

Note: The states of Assam, Goa, Manipur, Sikkim, and Telangana and the union territory of Andaman and Nicobar Islands do not report at the district level in their respective state bulletins. So, I have presented data for these states at the state level even when presenting district level insights. The National Capitol Territory of Delhi does report at the district level but I have aggregated data for the city of Delhi for ease of visualization.

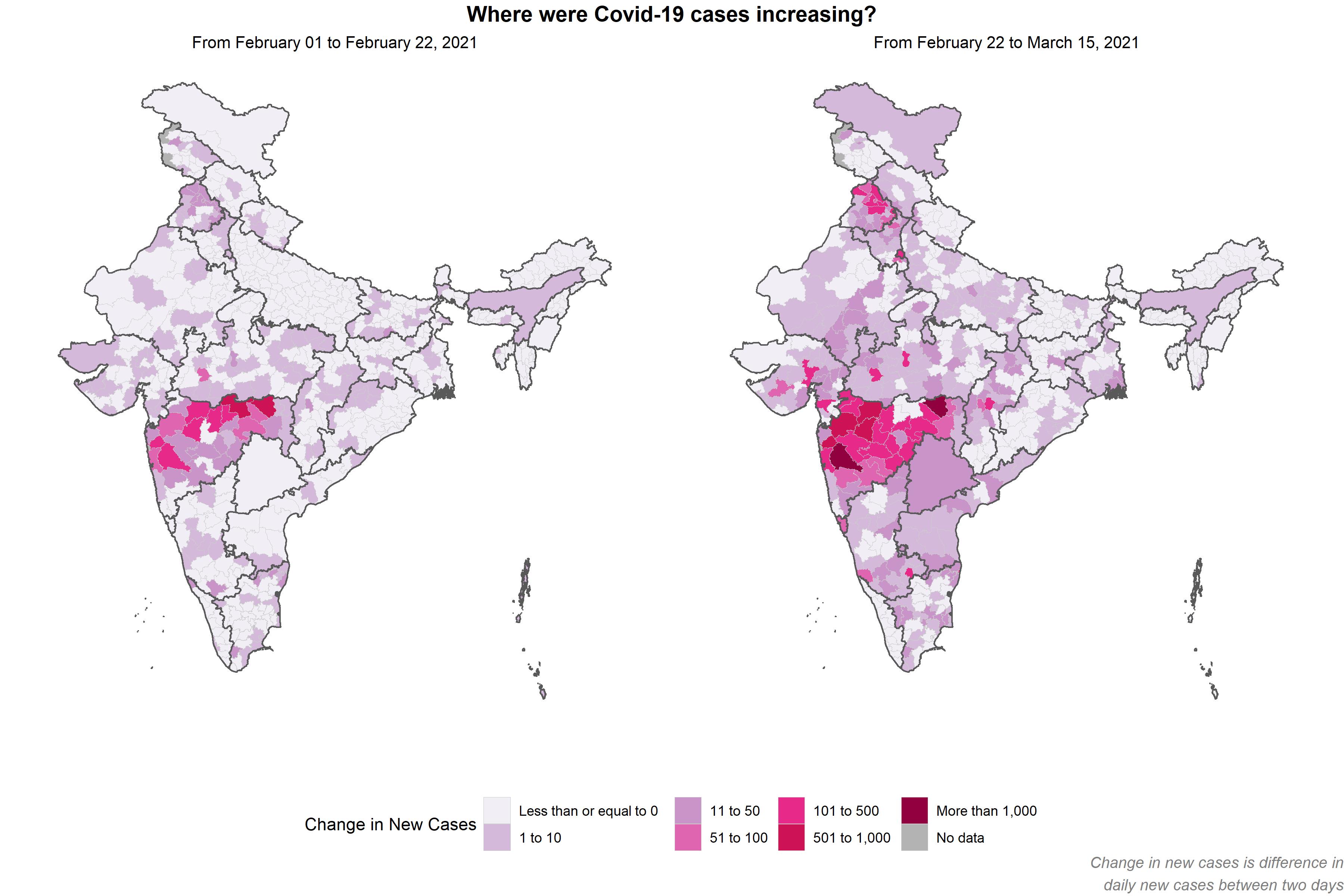

Rising cases

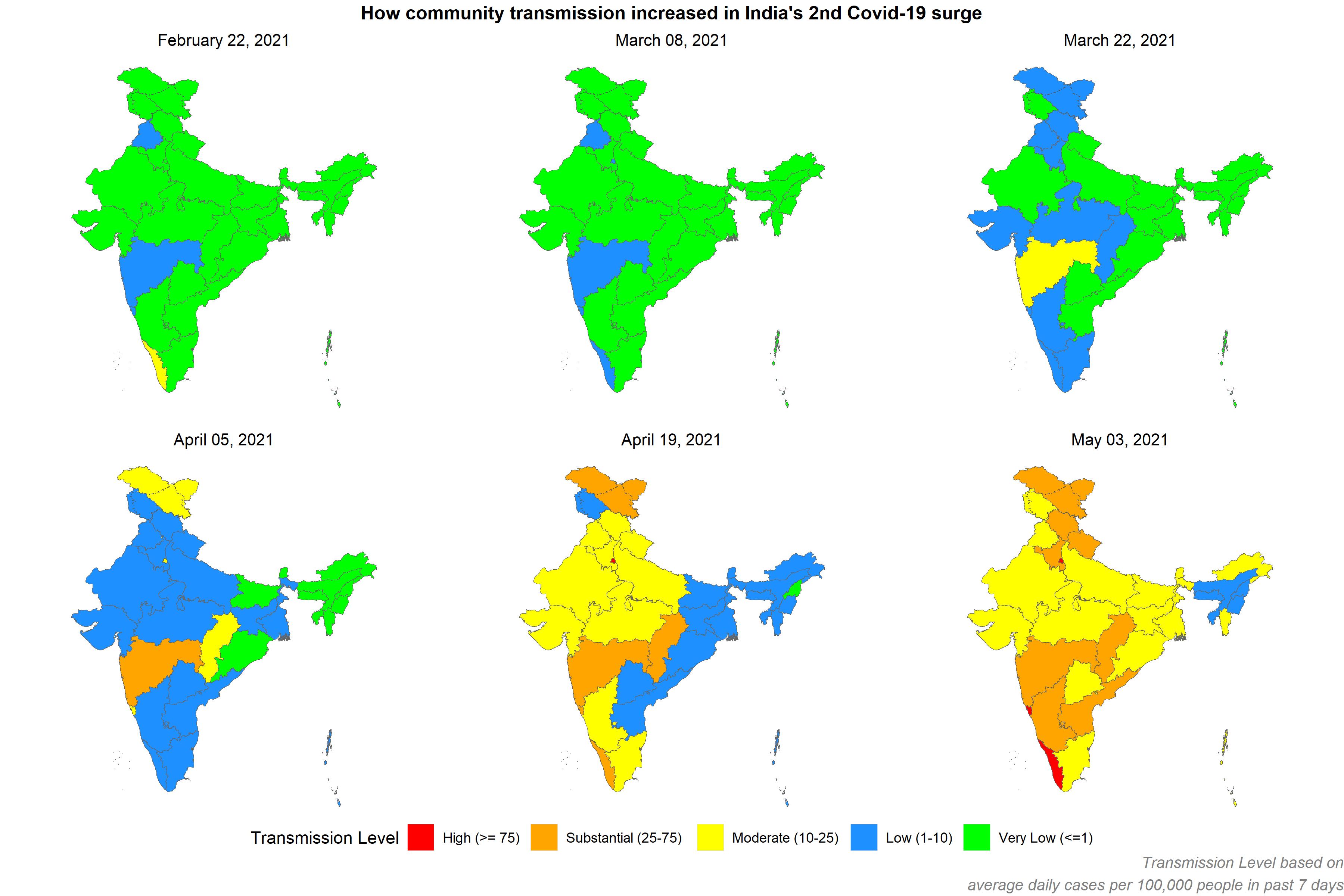

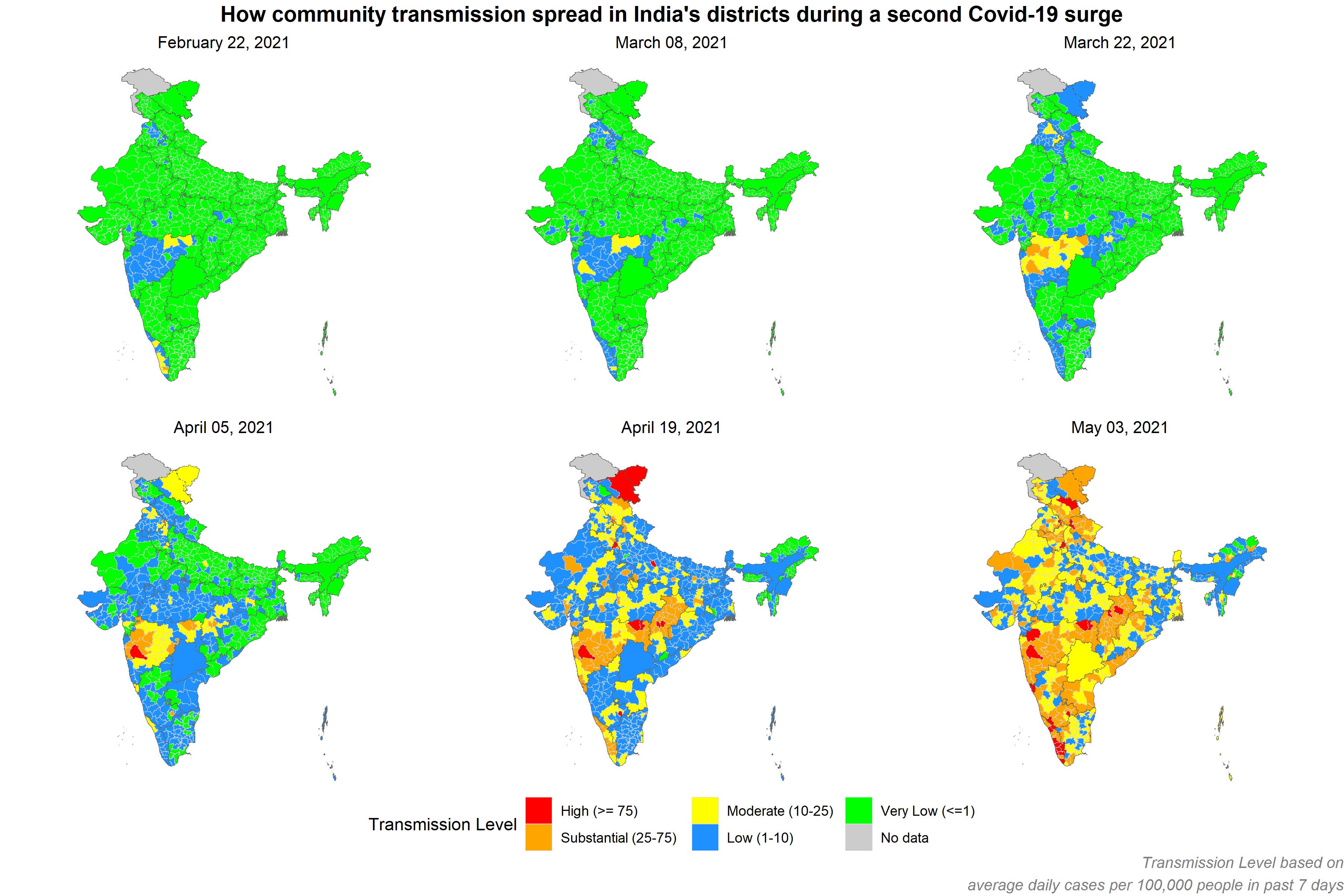

It is evident now that India’s second Covid-19 surge began in February. Maharashtra was experiencing a widespread rising wave of Covid cases in the three weeks ending on February 22, 2021 (see map below). Districts in the interior of the state including Amravati, Nagpur, Akola, and Jalgaon, and the dense urban districts of Pune, Thane, and Mumbai were clearly exhibiting an alarming trend compared to the rest of the nation. Some districts in Punjab and Tamil Nadu were also beginning to see a rise in cases (it later turned out the B.1.1.7 variant, first identified in the U.K., was more prevalent in Punjab). The increase in new cases rapidly rose from February 22 to March 15, 2021. By this time Delhi and Bangalore and districts in Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh, Goa, and Chattisgarh were major hot spots.

Deaths due to Covid-19 lag reporting of cases. And the reporting of cases itself lags when the disease may have been contracted. That is, the data is a collection of delayed indicators, and so the problem was already present before the first signals were apparent.

Case rate

As absolute number of cases doesn’t allow comparisons between regions (100 cases in two districts where one has two times the population of the other implies differing levels of spread). Case rate –– average number of daily cases in the past 7 days per 100,000 people –– provides an indicator relative to population which can then be compared across regions.

At the state level, Maharashtra, Kerala, and Punjab had case rates between 1 and 10 per 100,000 people. These are populous states with high density in several districts, and so, this in itself is a warning sign.

At the district level, hot spots were emerging in few other states including Goa, Chattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh, and Gujarat by early March. Note, these are bordering states and so movement of people very likely played a role in disease spread.

Mapping the case rate by district shows:

- Clearly increasing case rate from February to March to April 2021.

- Surging case rate in rural Maharashtra and its urban districts of Pune and Thane (seems to be have been ignored at the national level).

- Delhi and Bangalore exhibited early visible upward trends.

- A surprising reduction in cases in Kerala from Febrary 22 to March 22, 2021 and then a dramatic spike by mid April.

- An alarming increase in Ladakh in the northernmost edge of the country in late March, which then exploded by April 19. This one is especially notable as Ladakh is a relative less populated state and in the winter months does not experience tourist traffic, the dominant driver of its economy. So, any sign of increasing cases in Ladakh should have raised an alarm for closer investigation.

Transmission Levels based on Key metrics for Covid Suppression by Harvard Global Health Institute and others.

Undercount

While the Indian government reported ~ 4,000 deaths a day in early May 2021, it is highly unlikely this is accurate. Experts have estimated the total death toll to be 3-5 times higher.

The reasons for this are quite obvious. People have died at home or on the streets. These are not in the offical count. Creamtoriums or burial grounds in this surge are unlikely to have kept accurate counts or records. Even hospitals would have had trouble keeping up with data collection and reporting amidst such a devastating surge of hospitalizations and deaths. Many will have died of Covid but not have had a positive test. Many will have died of post-Covid complications (recovered from Covid and then died of other complications potentially caused by Covid) and will not be in the official death count. Then there is the strong likelihood of willful underreporting, the scale of which is yet unknown.

Unexpected surge? Yes, if you ignored the data

Governments and organizations like to proclaim they are data-driven. But nothing is really data-driven. People drive. People chose how they elect to use the data. So, while data can inform, people have to want to be informed. Especially politicians and policy makers.

As for me, having looked at just the available data (which is at a minimum incomplete, and worse, intentionally withheld) in a simple but fundamental way, I see enough signals that would have encouraged me to ask a whole lot of questions. Why an unexplainable drop in cases in late 2020? Why a slight uptick at the national level in February? Why a spike in cases in rural Maharashtra? In Punjab? In Goa? In Kerala? Was it the movement of people? Visitors from overseas? Instead of broadcasting a high recovery rate (a questionable metric to begin with), the question to have asked was is testing sufficient? What is the rate of false negatives in testing?

And never mind the increasing hospitalizations and ICU bed shortages, and lack of medical oxygen. The limitations of an inadequate healthcare infrastructure were no secret well before the surge. The risks India faced in the event of a surge were well advertised for those who were listening. The surge only exposed it all wholesale.

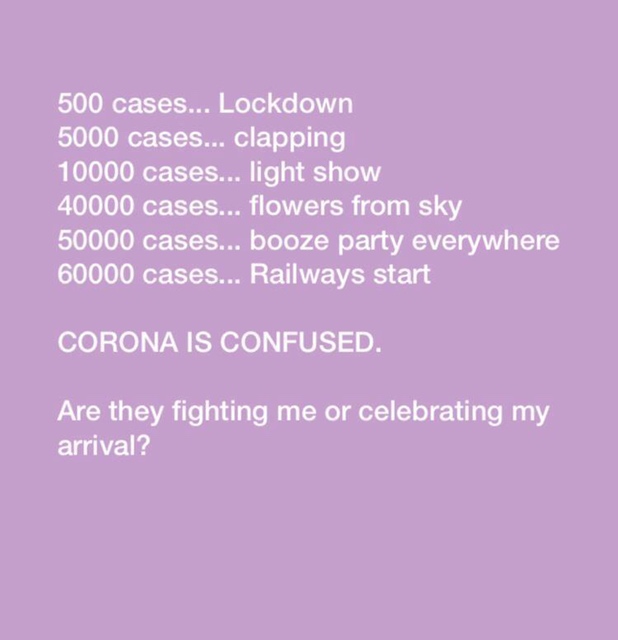

What was seemingly a flippant image floating on Indian WhatsApp message threads in May 2020, retrospectively is a simple but agonizing juxtaposition of data and (in)action. It highlights the various policy and (manufactured) public feel-good events occuring in early 2020 as cases increased.

What was seemingly a flippant image floating on Indian WhatsApp message threads in May 2020, retrospectively is a simple but agonizing juxtaposition of data and (in)action. It highlights the various policy and (manufactured) public feel-good events occuring in early 2020 as cases increased.

On May 11, 2020, when India reported a total of 70,768 cases to date, the Indian government resumed a portion of inter state rail service. Much of India’s lifeline is its rail-based movement of goods and people. It is also a guaranteed superspreader in an infectious disease scenario.

The thing with data is you have collect it honestly and reasonably accurately, ask appropriate questions, and then listen to what it is telling you. Often, the simplest of analysis is sufficient to generate the necessary alerts prompting detailed analysis or intervention. The supermodel that predicted the achievement of herd immunity (mentioned earlier) is a great example of an overtly complicated model whose assumptions weren’t fully vetted, and its performance not monitored with changing conditions (model validation and ongoing monitoring anyone?)

India’s political establishment’s handling of Covid-19 in many ways reminds me of the erstwhile Soviet Union’s handling of the Chernobyl disaster in 1986. Ignore the known facts and experts’ assessment, refuse to acknowledge the uncertainty and unknowns, selectively use data, project unfounded state efficacy in anticipation and management, conceal or choose not to advertise the severity of the situation and its threat when known, reluctantly (but with tragic delay) accept reality after the obvious “fallout,” engage in cover-ups and denialism, and eventually end up with a devastating crisis and loss of life that could certainly have been mitigated if not prevented.

Indian politicians should be well advised from this experience to not tout unfounded exceptionalism, declare premature victory over a public health threat (or any other threat) that is not well understood, and most certainly reject triumphalism over measured confidence.

India and its people are incredibly resilient. They will dig out of this crisis. As long as its politicians let them and help them.

References and Notes

- Data sources

- covid19india.org

- Harvard University’s Geographic Insights Dataverse

- I performed all data analysis and visualizations in R.

Comments